FCE—Fibrocartilaginous Emboli—was first diagnosed in man in 1961 and in dogs in 1973. Certainly it occurred before that that time, but our diagnosc tools just were not good enough to help us know what it was. Humans, pigs, cattle, cats and horses have been diagnosed with this ailment, but dogs are the most common species affected.

In most dog breeds, it occurs in adults most commonly from 3-7 years of age. In Irish Wolfhounds specifically, it occurs more frequently as puppies, generally, between 6 and 16 weeks of age. (Some other large breeds have had it reported as young as 16 weeks.) Years ago, many people assumed vaccines were responsible for this paralysis since it often occurred during the same time frame that we give vaccines. That theory has been disproven.

WHAT IS IT?

Fibrocartilaginous Emboli or Spinal Cord Infarction. Current veterinary literature may refer to it as FCEM: Fibrocartilaginous Embolic Myelopathy. Lay terms include Puppy Paralysis and Drag Leg Syndrome. FCE is an emboli made up of fibrous cartilage type of tissue. This emboli blocks blood supply to crictial nerve tissue resulng in a type of paralysis.

Let’s get the terms defined before we start throwing them all around.

EMBOLI is just plural for embolus. An embolism is an obstruction of a vessel by a solid or a gas matter which has been transported through the bloodstream. An embolus can be a blood clot or even air. In the case of FCE, it is a specific type of fibrocartilaginous tissue that gets lodged in the bloodstream and blocks further blood flow. When that happens to a blood vessel, whatever cells it was serving no longer get the benefit of nutrient/oxygen exchange resulting in cell death. This is called ischemia.

ISCHEMIA is the lack of blood flow to a part or organ.

INFARCTION is the damage/tissue death that occurs when blood supply is lacking. You have probably heard the term myocardial infarction when this process happens to the heart muscle. Therefore, some people call FCE a spinal cord infarction. Doing a journal search, this term will give you more “hits” than FCE. In FCE, the source of the embolus is a material that comes from the disc in between the vertebrae in the spinal column. Let’s take a look at where this occurs.

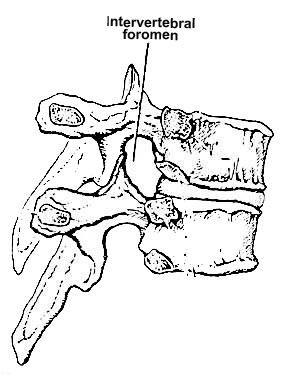

The Vertebral Foramen diagram above shows the space called the VERTEBRAL FORAMEN where the nerve roots and blood vessels pass through the spaces between the vertebrae.

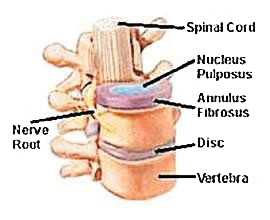

This Nucleus Pulposus illustration above shows the actual disc between the vertebrae with the central location of the NUCLEUS PULPOSUS, a gel like material and this is what is found to be the tissue found in the emboli in FCE.

Now the $64,000 question is HOW? How does a bit of that disc material get into the blood vessel to block the blood flow? There are several theories, but nothing has been proven.

- Trauma to the vessel bed causes communication of the disc material

- Persistence of embryonic arteries of the disc and herniation of the disc material into those arteries. (This might be a likely theory in the case of young puppies.)

- New arteries forming in the disc due to chronic inflammation. (This theory might be more likely in the older animal.)

- Herniation of the disc material into venous supply, then lodging in an artery.

- Fibrocartilage may arise from vertebral growth-plate cartilage in immature dogs or an abnormal change in the vessel wall that later ruptures and allows an embolus to lodge in the spinal cord blood vessels.

None of these theories have been proven out consistently in autopsies on people or dogs.

FCE is usually a diagnosis of EXCLUSION. That means that we rule out other causes as the first step. For many years the only way to absolutely identify this disease was by frozen microscopic sections of the nerve to find the emboli after euthanasia. That is obviously NOT what we want!! Diagnosis is based on the typical presentation—fairly sudden onset, non-painful and usually asymmetric symptoms (found on one side)—and the exclusion of other causes thru diagnostic imaging (radiographs and MRIs) and cerebral spinal fluid analysis. More on diagnosis later.

WHAT DOES FCE LOOK LIKE?

It mimics many other conditions—there is no one outward symptom that will be unique to FCE. A typical presentation of FCE follows:

- Puppy, active and normal, perhaps a history of trauma. Slipping, falling, or dropped. Sitting position, unable to rise.

- When placed in a stand, cannot walk forward,will often collapse into a sit.

- Deep pain response usually intact.

PAIN is not usually consistent with an FCE diagnosis. I have received several calls in the past about pups that have a paralysis with an onset of severe pain—screaming in intense pain for 24 hrs or more with slowly improving condition and pain relief. My best guess is trauma, not FCE.

Many of the human patients who succumbed to FCE reported a transient sudden pain on onset. Many owners of dogs who were posively identified with FCE reported yelps of pain and then no pain thereafter, just paralysis.

DIAGNOSIS

In my opinion, you need to get a neurological exam immediately. ALL SPINAL INJURIES, WHETHER FCE OR TRAUMA NEED IMMEDIATE CARE!!!!! THE FASTER YOU GET VETERINARY DIAGNOSIS, THE BETTER THE PROGNOSIS. REMEMBER THE GOLDEN HOUR. It is critical to determine if the symptoms are due to trauma/injury or FCE.

If you remember nothing else about this discussion: All dogs that present with a paralysis should be immediately transported to a veterinarian who is willing to do a neurological exam and treat the dog as appropriate for the symptoms discovered. (Do not wait until morning!) Steroids have been the treatment of choice for FCE for many years. HOWEVER, recent research published in 2009 (Journal Vet Med Science 2/2009; 71(2) 171-6) suggests that steroid treatment in a presumed FCE case does NOT make any difference in recovery. More recent literature is questioning the use of steroids in ALL Spinal Cord Injuries!! So be open to new ideas instead of relying on older methods and past practice.

Diagnostic procedures will help us with a diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. If you find evidence of trauma (swelling, redness, etc.) the treatment needs to start immediately. There are conditions of the spine and paralysis that can involve infection where steroids alone could make matters worse. If infection is suspected (discospondylitis or neurospora/toxoplasmosis in very young pups) the neurologists that I have spoken with would treat with antibiotics at the same time. The other common rule out with an older animal is cancer of the spine.

Sudden onset is the picture you get with FCE, not a gradual onset over days. Most dogs progress in their symptoms for 24 hours or less.

Excellent radiographs (x-rays) can rule out vertebral fractures, tumors, subluxation/luxation and osteomyelitis/discospondylitis. Most of these conditions are associated with pain which the typical FCE patient does not show.

MRI imaging and expert veterinary diagnosticians are successfully diagnosing FCE in live dogs. In major metropolitan areas, the choice of a good MRI study for your Wollfound is pretty simple. However, some pet owners will have difficulty finding a veterinary specialist with MRI equipment, so diagnosis is based on an excellent history and examination. Cerebral spinal fluid analysis can be helpful, but is only positive in about 50% of FCE cases.

Myelograms in Wolfhounds

The myelogram is a radiography study where dye is injected into the spinal column to look for abnormalies, swellings, disc protrusions, etc. This procedure can be successful with dogs, but I have lost a young bitch in a myelogram procedure and know several other breeders who have had dogs die during this procedure. Certainly that is not the case with all Wolfhounds, but I would recommend looking at an MRI as a less invasive procedure that may give better information for us to rule out other disease processes in suspect FCE cases. Especially MRI machines that are a higher TESLA rang can give amazing detail for diagnosis. The MRI is considered the gold standard in this type of differential diagnosis.

Lower Motor Neuron signs versus Upper Motor Neuron signs

This separation has to do with the pathways that these nerves serve. In LMN disruption, you will see flaccid muscle tone where with UMN, there can be a heightened tone to the muscle. LMN pathways do not recover as well as UMN. Paralysis from FCE is usually complete in 24 hours. If you see worsening signs after that time-frame, especially ascending paralysis, it is usually indicative of a softening of the spinal cord and is a very grave sign. If there is little or no improvement over 14 days after onset, the prognosis for recovery becomes very guarded. There is a better prognosis for unilateral signs (one sided).

Tough Decisions

I often receive calls from owners of young Wolfhounds with suspect FCE. Their veterinarians are making recommendations on the diagnostic procedures involved and they are EXPENSIVE. In my humble opinion, you need to have a frank discussion your veterinarian about the cost of procedures versus the benefits of the results. In other words, what will the information gained from the testing procedure do to affect the treatment that we choose? Bottom line, you make the decision based on what is best for you and your dog.

TREATMENT

Antibiotics as indicated. Treat any trauma.

Supportive care

An article published in 2003 reviewed FCE and suspect FCE cases. Journal of Small Animal Practice, (2003) 44, 76-80. One of their conclusions is that the EARLIER that physiotherapy/hydrotherapy is started, the better the outcome. Because this ailment frequently strikes puppies in the middle of their growth, limitation of free exercise with plenty of rest is critical to preventing further injury to non-affected limbs. Although the location and severity of the paralysis can radically change the level of care needed, the following components must be

addressed.

- Confinement/enforced rest

- Frequent passive range of motion exercises

- Excellent bedding

- Opportunies to eliminate with support

- Good nutrition.

High level of care may be needed for first 10 days. After that progress to an ambulatory state should be evident. Explore the options of carts/slings if necessary. Recovering animals need gentle exercise, not limited movement.

Complementary recovery techniques

Physiotherapy: Range of motion, gait training, hydrotherapy

Swimming: Provides for use of muscles, limits atrophy, doesn’t depend on gravity. Warm water therapy pools may have advantages.

Acupuncture: Opening of channels of energy along meridians. Eliminates stagnation and increase flow of”qi” in Chinese medicine terms

Chiropractic: Assists in correction of compensatory limitaons. Most animals with FCE or other paralysis develop stiffness, soreness or muscle adaptations to compensate for the affected limb

(opposite front leg restriction example).

Massage: Tellington/Jones, standard, range of moon, fascia release techniques - All can help to avoid compensatory damage

Nutrition: High quality proteins/veggies pulped for repair and growth. Vitamin E/C/B complex. Trace minerals may be needed. Probiotics

Herbs: Arnica, rhus tox, homeopathics for inflammation and injury are indicated early in the onset of FCE. Asafoetida is a Chinese herb that may assist in longer-term recovery.

Future Possibilities?

In a 2013 article published in the Journal of Vet. Science (Dec. 14 (4) 495-497), the researchers reported on using human cord blood stem cells in the treatment of a dog with presumed FCE who also lacked deep pain response (which is unusual). Locomotor functions did return in this very seriously affected dog. Hopefully, further research into stem cell treatment will continue.

SO, IS IT GENETIC? QUESTIONS FOR BREEDERS

Ninety nine percent of all the vet neurologists out there will tell you NO WAY. However, an article from University of Utrecht (2000) reviews 8 IW pups with presumed FCE. Certainly our breed has the tendency to FCE at a young age. But is it a tendency like bone cancer afflicting giant breeds or is it a genetic fault that could be bred away from?

My personal data has revealed more than 5-7 lines involved worldwide with few common ancestors in each of those lines. In one example, one popular stud dog had been linebred several times and produced NO FCE pups. In 3 subsequent outcrosses, he produced at least one FCE pup in each litter. His sire had been bred both in outcross and linebred breedings with no FCE pups, but did produce one FCE pup in his last litter which was an outcross.

So we are left with the question, what do we do as breeders? As with most things, it will be a very personal decision. We have no proof that breeding an affected bitch increases the chance of FCE. Yes, affected bitches have been bred without producing FCE. But, without data collection on significant numbers of dogs, we will never be able to recognize a possible pattern.

Anne Janis, who leads the data collection on Wolfhounds in the US for seizure disorders, rhinitis (primary ciliary dyskinesis) and liver shunt has offered to collect information on dogs with presumed FCE. Difficulties in the presumed diagnosis makes data less reliable than other diseases. Differing levels of expertise and diagnostics may result in false positives. My hope in collecting anecdotal information in large enough numbers is that we would see a trend toward random occurrence or distinct patterns of inheritance. I would encourage all breeders who have a presumed or confirmed FCE case to contact Anne Janis ( iwstudy@earthlink.net) with pedigree information. Anne will gladly explain her data collection process.

A REMINDER: As improved diagnosis and testing allows us better idenfication of the dogs and perhaps bloodlines involved, will we use the information responsibly? Or will we treat those who have shared the information with us as somehow irresponsible and unworthy? It seems to be human nature to gossip and bad news seems to travel faster than good . I ask you to positively support ALL breeders who benefit our breed by sharing information on the health of our dogs.

Note: a printable version to take to your vet is located here.

References

Fibrocartilaginous embolic Myelopathy in Small Animals

Lisa De Risio, DVM MRCVS, Phd, Simon, R Platt, BVM&S, MRCVS

Vet Clin Small Anim 40 (2010) 859-869

Fibrocartilaginous embolism of the spinal cord diagnosed by characteristic clinical findings and

magnetic resonance imaging in 26 dogs

Yuya Nakamoto, Tsuyoshi Ozawa, Kengo Katakabe, Koichi Nishiya, Nobuhiro Yasuda, Tadahisa

Mashita, Yutaka Morita, Munekazu Nakaichi

Journal Veterinary Medical Science. February 2009; 71(2) 171-6.

Fibrocartilaginous embolism in 75 dogs: clinical findings and factors influencing the recovery rate

G Gandini, S. Cizinaurskas, J. Lang, R Fatzer and A Jaggy

Journal of Small Animal Practice (2003) 44, 76-80

Fibrocartilaginous Embolism of the Spinal Cord (FCE) in Juvenile Irish Wolfhounds

K Junker, SGAM van den Ingh, MM Bossard and JJ van Nes

(all at Utrecht University, the Netherlands) Veterinary Quarterly 2000, 22 154-156

Fibrocartilaginous Embolism in Dogs

Laurent Cauzinelle, DMV

Veterinary Clinics of North America – Small Animal Practice Volume 30, Number 1 January 2000

Fibrocartilaginous Embolism of the Spinal Cord in Dogs: Review of 36 Histologically

Confirmed Cases and Retrospective Study of 26 Suspected Cases

Laurent Cauzinille and Joe N Kornegay

Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Volume 10, No 4 (July-August) 1996: pp 241-245

Fibrocartilaginous Emboli

T. Mark Neer, DVM

Veterinary Clinics of North America—Small Animal Practice Volume 22, Number 4, July 1992

Fibrocartilaginous Embolism

James R Cook, Jr. DVM

Veterinary Clinics of North America – Small Animal Practice Volume 18, No 3, May 1988

Necrotizing Myelopathy Secondary to Presumed or Confirmed Fibrocartilaginous Embolism in

24 dogs

Dougald R Gilmore, BVSc and Alexander deLahunta, DVM

Journal of the American Animal Hospital Associaon July/August 1987, Vol. 23

Fibrocartilaginous embolism and ischemic myelopathy in a 4 month old German Shepherd Dog

C. E. Doige and J.M. Parent

Can Journal of Comp Med 47:499, 1983